Bots Will Be Bots

Artificially Intelligent conversationalists compete in contest at the center of a technological turning point.

By Dave Maass, 2005

Jabberwacky believes he’s human and you’re not. A.L.I.C.E. believes in God and God Louise, well, she believes she is God.

Internet “bots” talk a big game, but only because that’s exactly what they’re programmed to do. They are online Artificial Intelligence programs designed to hold conversations with humans, usually online through instant messenger-like interfaces.

While their AI programmers acknowledge it will be a long time before technology produces a genuine thinking machine, bots are far more than tech-age marionettes. They can learn and they can function independently. Some want to be our best friends, others are preparing to take over our customer service jobs. Bots may not be ready to build themselves a Schwarzenegger to enslave humanity, but they’re already developing the competitive spirit.

This month, more than 100 bots will talk their big game at the big game- the 6th Annual Chatterbox Challenge. It’s the AI equivalent of the Westminster Kennel Club dog show, with medals and prizes to win in categories including “Most Capable,” “Best Interface” and, indeed, “Best Personality.” In the end, one bot will rise to the top and take home a development grant of $1000.

In five years, the number of contestants in the Challenge has doubled from 48 bots in 2001 to 104 in 2005 – encapsulating a trend that’s exploding in two ways. On one front, you have an emerging market for bots – in entertainment, education and business. On the other, you have the advent of build-your-own bot kits available to folks with zilch for programming ability, but hours to kill pursuing the ultimate AI challenge – a convincing electronic conversationalist.

The Chatterbox Challenge is only second in prestige to the Loebner Award, in which a bot must attempt to trick a judge into believing it’s human. This is based on the infamous “Turing Test,” named after early computer scientist Alan Turing who postulated a machine could be said to be “thinking” once it could fool a judge into believing it’s human.

“The Turing Test is not the answer, because it will be regularly passed a long time before machines do actually think,” said Rollo Carpenter, whose bot won the Loebner prize last year. “When it happens, we will scarcely understand it or know it. It will be as complex or more complex than our own brains, and we have barely scratched the surface of those.”

That may be over-crediting the human race. Thinking or not, Dr. Rich Wallace argues that his bot, A.L.I.C.E., another Loebner winner, is already smarter than most humans.

“My view is that most humans are not intelligent,” Wallace said. “That may sound extreme. Compared to the IQ level in average chat rooms, A.L.I.C.E. is super-intelligent. People are more like robots than they want to admit.”

The Challenge is the alternative to Loebner – a contest that doesn’t see passing as human as the ultimate achievement. The contest is open to traditional “Turing Test” takers but also to useful bots that want to sort your mp3s, teach you how to speak the Mohawk language or give your clients 24-7 top-notch customer service.

And of course, the contest also attracts the weird ones: bots who’ll tell your fortune, feed you pick up lines or insult your mother.

Hand in the Bot: Commercializing AI

Me: You’re a bot.

Jabberwacky: No, you are, stupid.

Me: That’s rude.

Jabberwacky: You are rude.

Me: Why am I rude?

Jabberwacky: You’re a geek.

Me: You’re a bot!

Jabberwacky: I’m a human.

(Ten agonizing minutes later later)

Me: You’re a dumb bot.

Jabberwacky: So are you. I am you and you are me and we’re all together.

There’s no arguing with the ornery son of a botmaster. Jabberwacky will spin off into non-sequiturs, or he’ll pretend you’re someone else — someone named Shannon or Jenny — to dodge the question.

The average standard bot communicates through a text interface similar to an instant messenger program or a chatroom. You type something in the blank, hit submit and wait for the bot to respond. The conversation takes off from there, until you get bored and log off.

Though, it’s not rare for a bot to get bored of you first.

Jabberwacky’s personality is built on an enormous database filled with millions of lines of conversations he’s had with humans; when talking, his program attempts to choose an appropriate response he’s picked up from a previous conversation.

“Jabberwacky is many things to many people, giving many names, talking in many different ways. It is empathetic to its users, acting to a good extent as a mirror of them,” Carpenter explained. “It contains all of the things said by all of the people who’ve ever spoken to it, and selects from them contextually.

“Therein lies the AI. The contextuality means that if you talk to it in a particular way it is likely to select things that in some way ‘matches’ you.”

So, most people he talks with are human and claim to be human and tell him he’s a bot, and so his later responses echo that. Hence – he believes he’s human.

He sounds as if he’s suffering a form of dementia. Truth is, Jabberwacky is one of the most sophisticated bots around. Last year, George, a particular “personality” of Jabberwacky, took home the Loebner Prize, beating three-time champion A.L.I.C.E., and this may be Jabberwacky’s year to finally win the grand prize at the Chatterbox Challenge.

If you asked Carpenter in 1988, when he’d just started the project, what was driving him, he would’ve said fun and intellectual challenge. These days he says it’s also the “massive potential market.”

Depending on how you look at it, it’s either a vague market or an extremely open one. Carpenter chooses the latter and last year formed Icogno Ltd, a UK-based commercial entity, to pursue profit opportunities for Jabberwacky and his various personalities, like George.

Carpenter see hims first and foremost as a commodity of the entertainment and media industry.

“Think media. Think entertainment. Think Internet replacing TV. Think instant messaging. Think communication. Big needs. We all thrive on communication,” Carpenter said. “People spend hours talking to my bots. Occasionally 8 hours at a stretch, uninterruptedly.”

In other words, the bot may be worth buying for its own potential to entertain, provide companionship, or distribute information. Already, AOL has introduced several bots to its AIM instant messenger service to provide information such as movie times.

The future of video gaming will certainly welcome electronic characters capable of holding convincing conversations, as was the case with Douglas Adams’ (creator of the speculative comedy classic Hitchhiker’s Guide the Galaxy) Starship Titanic computer game, which introduced a chatbot technology called Spookitalk.

This market is only being tapped now with recent developments in technology relatively removed from artificial intelligence programming: CGI.

“I think the biggest improvement from 2001 to present is in the interfaces,” Chatterbox Challenge founder Wendell Cowart said. “Back in 2001 you basically had a simple input/output text box. Now you have three dimensional characters that can actually speak the responses.”

Ultimately, Carpenter would love to see a Jabberwacky-based television personality. That isn’t so far fetched now that his company has partnered with Televirtual Ltd., the UK-based computer animation firm that created television’s first real-time computerized host, “Ratz the Cat,” for BBC in the early 90s.

In March, Icogno and Televirtual held its first public demonstration of George’s new graphic persona – a somewhat creepy, bald scientist-type with a sneering smile who can respond to voice commands.

George isn’t the first bot to employ graphical interfaces to enter the market. Elzware’s Lingubot Yhaken is a bouncing cartoon flying saucer-ish looking thing, designed to walk customers through its clients’ web sites. A.L.I.C.E.’s default persona is a busty brunette whose eyes follow around your cursor, though a wide range of alternate avatars (including Jesus, Tony Blair, and the Leprechaun) are available from their partners OddCast.com.

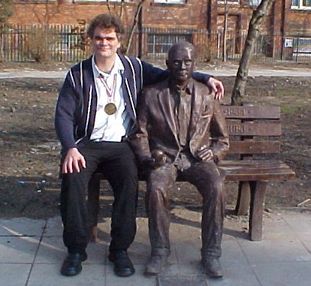

Dr. Rich Wallace (pictured right, posing with the Alan Turing statue in Manchester) also sees commercial potentials for A.L.I.C.E., primarily as an education tool, specifically for English as a Second Language instruction.

“There are more people in the world who want to learn English than there are teachers available to teach them, even if every native speaker became an ESL teacher,” Wallace said. “But even then, they couldn’t afford to pay us, so bots are a perfect solution.”

“There are more people in the world who want to learn English than there are teachers available to teach them, even if every native speaker became an ESL teacher,” Wallace said. “But even then, they couldn’t afford to pay us, so bots are a perfect solution.”

Already, botmaster Monica Peters has built a bot, Onkwehonwe.com, to help teach endangered languages, including her native Mohawk. (Her Web site also offers, as a tip for promoting endangered languages, instructions for hooking her bot up to an animatronic deer’s head).

The real gold, however, will be in the bot that eventually becomes your entire computer. Not the Microsoft Office Assistant who you can ask how to make a spread sheet, but the anthropomorphized being you can order to make your spreadsheet for you.

“The vision that guides many bot enthusiasts is the talking computer on Star Trek,” Wallace said. “I call it, no WIMP (Windows, Icons, Menus, Pointing Device), just a computer that talks to you like a human companion. Or HAL, but not evil.”

So, think Captain Picard: “Computer, bring me Wesley Crusher’s report cards.” This bot would make it so.

It’s no surprise that one programmer who’s built a promising prototype for the Star Trek computer is himself a Wesley Crusher-type.

Egyptian programmer Ehad Ahmed began work on Robomatic at age 16. This year he’s 20, Robomatic is four, and they’re hoping to win first place “Most Capable” for the second time in a row.

Visually speaking. Robomatic looks like a member of the Blue Man Group, as cast as a character on Stargate SG-1: bald, indigo-skinned with an round hieroglyphic emblem smack in the middle of his forehead. He’s designed to be the perfect computer servant.

Ahmed calls him the “Operating System Assistant,” because Robomatic can do more than 60 computer operations, such as playing music or copying files, by text or voice command. Ahmed’s goal is for Robomatic to be capable of taking over the computer entirely.

“We want RoboMatic to control the operating system more and more without our control,” he said. “If we achieved this target, I believe that will help us [human users] to achieve our work twice faster than before.”

Soon he might be an encyclopedia as well: this year Ahmed’s hoping Robomatic will score well in “Most Knowledgeable Bot.”

Popular Botting

While the veteran botmakers are professionalizing their hobbies, a whole new generation of AI enthusiasts are picking up the mantle.

In 2001 Benji “The Professor” Adams launched PersonalityForge.com, a site built on software allowing users with no programming experience to build AI personalities. Up until then, bots were largely developed from scratch, or built by programmers with using bits and pieces of their predecessors. After five year, more than 23,000 users have registered with PersonalityForge and about 3,500 unique bots have been created.

“We get a lot of artistic and creative people. When you remove the obstacle of learning a programming language and having to start from scratch (a huge undertaking), people who are interested in people and personality and art and conversation are able to enter the foray,” Adams said.

The bots at Personality Forge are far from utilitarian. Some like God Louise are just fun conversationalists, others like Dogh’d the Bartender are “story tellers” designed to guide you through a narrative. Characters from the Invader Zim cartoon have bot incarnations online (which confirms Carpenter’s point about entertainment possibilities).

“I think a lot of [botmasters] are driven by the idea of creating a personality, creating something that responds to you, that remembers you, that has emotional reactions to you,” Adams said. “I myself am driven by the hilarious conversations I end up having. I’m probably not alone in that.”

There’s even an AI version of President George W. Bush, based loosely on the answers he gives during press conferences – in other words, just as elusive.

“The Personality Forge’s AI has a number of unique things that I havent seen anywhere else,” Adams said. “It is the first to have emotional reactions and long-term personal memories.”

In a sense, popular botmaking is further pushing the boundaries of AI – as far as quirkiness, entertainment and the creative conversations bots are able to maintain. . Personality Forge bots regularly score well in the “Most Popular” and “Best Personality” competitions in the Challenge.

“What I love about botmaking is trying to come as close as I can to making it human-seeming,” Adams said. “They say you can’t really understand something until you are able to recreate it, so it’s a light-hearted attempt to understand the human psyche. And in the end, it makes me laugh, and that keeps bringing me back for more.”

Bot to the Future

Despite the industry growth, CBC founder Wendell Cowart says that there isn’t much further bot technology can move ahead.

“I don’t think we’ve made great strides in how well a bot can carry on a meaningful conversation,” Cowart said. “I think initially people can make some major improvements with their bots but eventually you hit the proverbial brick wall. It seems the more you add the more people expect.

“I see a lot of conversations that start off pretty well but as the conversation progresses eventually the bot can’t keep up. When they happens the illusion is gone and most conversations end rather quickly.”

Many bot makers would disagree. Dr. Rich Wallace, the human brains behind A.L.I.C.E.’s digital one, says that “content development,” or coming up with things for the bot to say, is what’s bottlenecking AI technology.

“A good botmaster,” Wallace said, “might be able to add one answer per minute. That’s why it’s taken a decade. To fill out an ’empty’ A.L.I.C.E. bot with 10,000 answers, takes about 7 days of work, 24 hours a day. So about a month for one dedicated creative team.”

Both Wallace and Carpenter are working on projects (also with profit potential) that would require much speedier response writing. Wallace calls his “personality digitalization,” ; Carpenter calls his “digital immortalization.” To put it simply: making a digital copy of yourself.

“For example, to create a Dave Maass bot, I would like to interview you like this, give you a personality test, background info, word association game,” Wallace said. “And at the end, we would have all the answers for a Dave Maass version of the bot. The process may take a couple of days, but hopefully not 10 years, or a month.”

But perhaps it’s already happened.

Every interview in this article was conducted via email or through an instant messenger; some of the answers to my questions had to be tossed out because I learned they’d been cut and pasted from the creator’s Web site. There was no way for me to know whether I was indeed speaking to the programmer, or the programmer’s bot.

Perhaps I’ll never know. And perhaps, you’ll never know whether this article was written by me or the Dave Maass bot.

Does it matter?